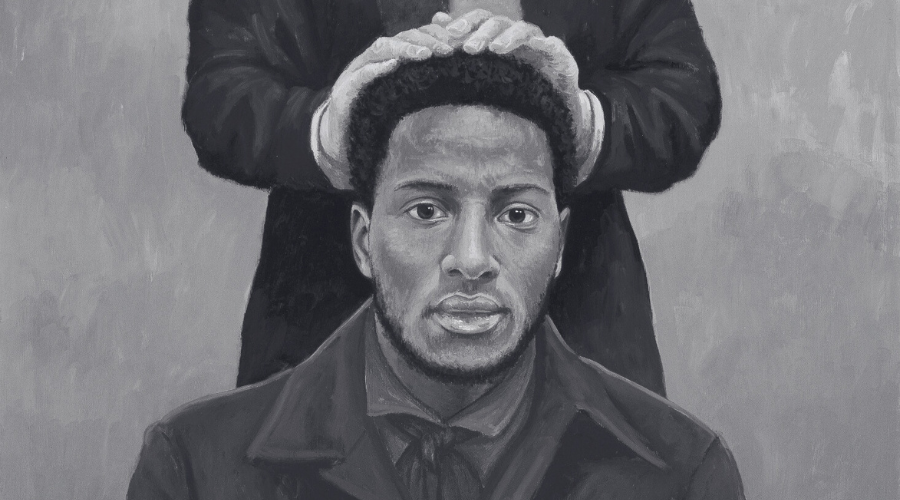

Blacks In Mormonism, Explained

Blacks in Mormonism: Blacks and Slavery in Missouri in the Early 1800s

The increased settlement of Church members in Missouri during the early 1830s caused concern among non-Mormon settlers who felt threatened by the growing numbers, political influence, economic impact, and cultural and religious differences of the Saints.Latest Posts

Blacks in Mormonism: Reasons Why Black Africans Were Restricted From the Priesthood Blessings

Declaration 2 announces the end of the restriction on black Africans and priesthood. The Official Declaration 2 is a declaration of a revelation – not the revelation itself – received in responding to problems, questions, concerns, culture, and pain points of God’s people as a whole in dealing with restrictions on Black Africans and Blacks in Mormonism and the priesthood.Read MoreExplore More Topics

Source Experts

Dr. Marcus Martins

Marcus H. Martins holds a bachelor’s degree in Business Management, a Master’s in Organizational Behavior, and a Ph.D. in Sociology, specializing in Religion, Race, and Ethnic Relations.

Dr. Casey Griffits

Dr. Casey Griffiths received a B.A. in History from Brigham Young University and went on to complete an M.A.

Kevin Prince

Kevin Prince is a religious scholar as well as a technology industry CEO and entrepreneur.

Dr. Bruce H. Porter

Bruce H. Porter has undertaken extensive research on behalf of the Religious Studies Center at BYU, with a specific emphasis on the Pearl of Great Price and the Book of Abraham.

Dr. Anthony Sweat

Dr. Anthony R. Sweat holds a BFA in painting and drawing from the University of Utah and achieved his MEd and PhD in curriculum and instruction at Utah State University.

Dr. Tyler Griffin

Dr. Tyler Griffin commenced his professional journey by teaching seminary for six years in Brigham City, Utah.

Marvin Perkins

Marvin Perkins is a distinguished global public speaker with a background in community engagement and religious education.

Dr. Scott Woodward

Dr. Scott Woodward has committed nearly two decades to educating within the Church Education System.